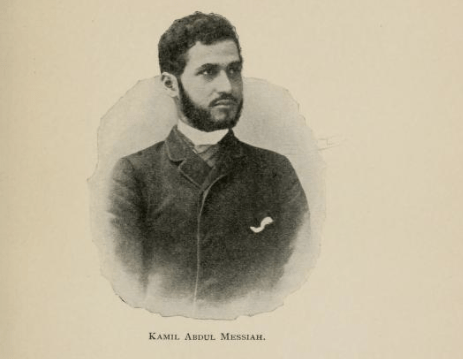

This essay, summarizing the inspirational story of Tokichi Ishii, is one chapter in A Bundle of Torches, coming back to print in January 2022 in the newest addition to the F. W. Boreham Signature Series. The full story of Tokichi Ishii, A Gentleman in Prison (1922) will also be returning to print. Ishii's remarkable story was first published in Japanese in 1919 under the title 聖徒となれる悪徒: 石井藤吉の懺悔と感想 ("The Scoundrel Who Became a Saint"). Editions followed in English (1922), Danish (1923), German (1924), Dutch (1925), Hungarian (1927), Chinese (1933), and Arabic (1980).

I

The spiritual pilgrimage of Tokichi Ishii is, Dr. Kelman declares, the strangest story in all the world. It is, he adds, one of our great religious classics. ‘There is in it something of the glamour of the Arabian Nights and something of the hellish nakedness of Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Horror. There is also the most realistic vision I have ever seen of Jesus Christ finding one of the lost. You see, as you read, the matchless tenderness of His eyes and the almighty power of the gentlest hands that ever drew a lost soul out of misery into peace.’

The story was first told in the saloon of the Empress of Russia. The cold winds swept across the sea, having a touch of the northern ice in them, and a group of passengers had gathered in a sheltered spot. They were relating to each other all kinds of experiences with which they had met. But, after a while, every narrative was overshadowed and driven into the oblivion of forgetfulness by the story that was told by Miss Caroline Macdonald, a quiet little Scottish lady. As soon as she had finished her amazing recital, everybody felt that they had been listening to one of the world’s most thrilling and absorbing romances. It is, as Mr. Fujiya Suzuki, M.P., says, just such a story as Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables. Tokichi Ishii is Jean Valjean over again, but Jean Valjean with a profound spiritual experience. Dr. Kelman, who was of the party on board the Empress of Russia, insisted that the story, which had already been published in Japanese, must be translated into Western tongues. And, as a consequence, here it is! It is worthy, as the publishers claim in their introductory note, to be cherished among the classical prison documents which are among the priceless treasures of the Christian Church. It is entitled A Gentleman in Prison; and he would be of cold blood and sluggish soul who could read it without deep emotion. Nor is its interest merely—or mainly—sentimental. ‘The most striking aspect of the book for many readers will be its psychology.’ Dr. Kelman declares, ‘One can imagine the glee with which Professor William James would have seized upon it and given it world-wide fame. The narrative discloses a true psychologist, full of curiosity about himself and bewildered by the masterless passions of his amazing soul.’ It has, too, a very high apologetic value. If I knew a man who had any doubt about the reality of religion, or about the existence of God, or about the eternal Deity of Jesus Christ, I would rather hand him a copy of A Gentleman in Prison than any volume of argument or of divinity that has ever been published. If A Gentleman in Prison did not scatter his scepticism, nothing would.

II

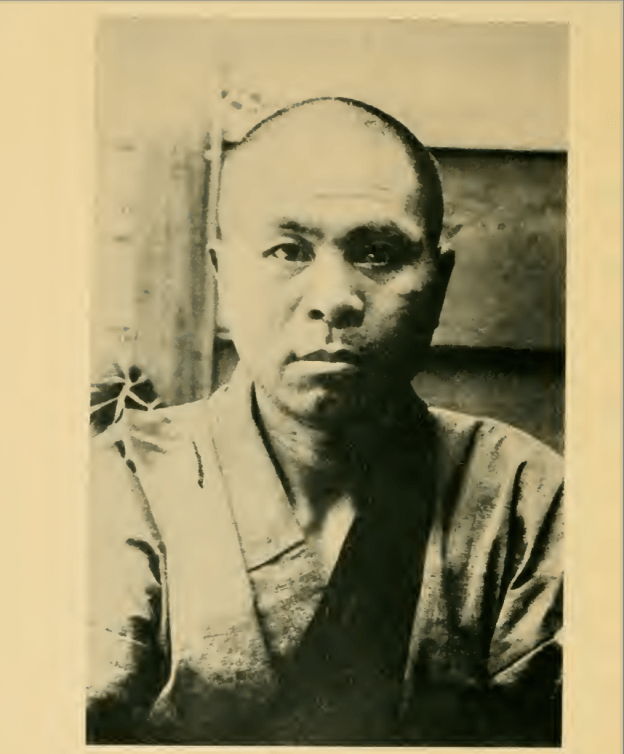

The book is dedicated To All in Every Land Who Have Never Had a Chance. Ishii certainly never had. He was born in heathenism; his father was an inveterate drunkard; his mother was the daughter of a Shinto priest. Up to the time of his death, he only knew two Christians; and he met them during the brief period of his last imprisonment, and after he himself had avowed his faith in Christ. At the age of thirteen he had to decide whether he would steal or starve. He resolved the problem in the way in which most of us, similarly situated, would have settled it. He stole. ‘This,’ he says, ‘was the beginning of my life of crime. As I look back now I realize keenly how easily a child is influenced by bad friends and surroundings.’ Stealing quickly led to gambling; gambling led to more stealing; and stealing and gambling together soon plunged him into prison. In prison he consorted with hardened criminals who laid themselves out to make the boy as callous as themselves. ‘The fact of the matter is,’ says Ishii, and he underlines the words, ‘the fact of the matter is that a prison is simply a school for learning crime.’ He was an apt pupil. During the years that followed, he committed one atrocity after another in the most shameless and audacious fashion. He spent most of his time in gaol; and, immediately upon his release, he committed some new felony or murder which once more brought the police upon his trail. And, on the twenty-ninth of April, 1915, his career of crime reached a hideous climax. He murdered the geisha girl who waited upon him at a tea-house near Tokyo. This, the most dastardly and dreadful of all his misdeeds, nevertheless had in it the germ that developed into better things.

III

Ishii crept away from the tea-house without leaving any clue that could lead to the conviction of the culprit. But, some time afterwards, when he was imprisoned on a later charge, he overheard his fellow-prisoners discussing the tea-house murder. A man named Komori, the lover of the girl, was, they said, being tried for the murder of the geisha. Within the grimy soul of Ishii a knight lay slumbering, and this startling news awoke him. ‘For a moment,’ Ishii says, ‘I could scarcely believe my ears. But upon enquiry I found that the men knew the facts, and that it was actually true that an innocent man—the lover of the dead girl—was on trial for her murder. I began to think. What must be the feeling and the suffering of this innocent Komori? What about his family and relatives? I shuddered to think of the agony that must have been theirs. I kept on thinking; and, at last, I decided to confess my guilt and save the innocent Komori.’

It is this quality in Ishii that led Dr. Kelman to call the book A Gentleman in Prison. ‘At his worst,’ the doctor says, ‘he retains the pride and honour of a gentleman; and, in the supreme test, insists on dying to save an innocent man. Cruel as a tiger, he yet responds, like a charming little child, to any kindness shown him. In the midst of a career of systematic and outrageous vice, he sometimes acts in a spirit which many of the elect might envy.’

During the days that followed his confession, Ishii laboured ceaselessly to establish Komori’s innocence by proving his own guilt. Never in all the calendars of crime did a man work so hard to prove his innocence as Ishii worked to collect evidence that would secure his own conviction. To strengthen his case, he made a clean breast of all his offences; and owned frankly that he was the murderer of several victims whose deaths had been shrouded in impenetrable mystery.

The trial of Ishii for the murder of the geisha girl dragged on for days and months. It was one of the most baffling cases in the criminal records of Japan. At length Ishii was found Not Guilty. ‘I was greatly disheartened about this,’ he says, ‘for I knew that if I were acquitted the innocent Komori would suffer the penalty of the crime. I was so distressed about it that I could not sleep.’ He instructed his lawyer to leave no stone unturned in getting justice done. In accordance with the provisions of Japanese law, he appealed against his acquittal; the case was reheard in the Appeal Court; and Ishii—to his delight—was sentenced to death.

IV

Like everybody else, Miss Macdonald, who lived in Tokyo, was profoundly interested in the strange case, and determined, if possible, to visit Ishii in prison. ‘Early in the morning of New Year’s Day,’ Ishii says, ‘a special meal was brought me instead of the ordinary prison fare; and I was told that two ladies—Miss Macdonald and Miss West—had sent it. Who could these persons be? I had never heard of them before. There was no reason why I should receive anything from people I did not know, and I told the official that I could not accept the gift.’ The gaoler induced him, however, to reconsider his proud decision. ‘The food was sent to me during the first three days of the New Year. A few days later a New Testament was received from the same source; but I put it on the shelf and did not even look at it.’ In the end, however, the monotony of his prison life proved too much for his pride.

‘I took the New Testament down from the shelf,’ he says, ‘and, with no intention of seriously looking at it, I glanced at the beginning and then at the middle. I was casually turning over the pages when I came across a place that looked rather interesting.’ It was the passage that tells how Jesus set His face like a flint to go to Jerusalem, although He knew that it was certain death to do so. The conception appealed to Ishii’s sense of daring, of gallantry, of adventure. He laid the book aside, but he resolved to dip into it again. When next he picked it up, it opened by chance at the story of the man who had a hundred sheep, and who, leaving the ninety and nine in the fold, went out into the mountains to search for that which was lost until he found it. Again Ishii was interested, though not quite as deeply as before. But he promised himself that he would give the little book a third trial. He did.

‘This time I read how Jesus was handed over to Pilate by His enemies, was tried unjustly and put to death by crucifixion. As I read this I began to think. Even I, hardened criminal that I was, thought it a shame that His enemies should have treated Him in that way. I went on, and my attention was next taken by these words: And Jesus said, Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do. I stopped. I was stabbed to the heart as if pierced by a five-inch nail. What did the verse reveal to me? Shall I call it the love of the heart of Christ? Shall I call it His compassion? I do not know what to call it. I only know that, with an unspeakably grateful heart, I believed. Through that simple sentence I was led into the whole of Christianity.’

On each of the following pages, Ishii harps upon his text. Every time he repeats it, it seems more wonderful to him. ‘The last words that a man utters,’ he says, ‘come from the depths of his soul; he does not die with a lie upon his lips. Jesus’ last words were: Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do; and so I cannot but believe that they reveal His true heart.’

‘I wish to speak,’ he says again later, ‘of the greatest favour of all—the power of Christ, which cannot be measured by any of our standards. I have been more than twenty years in prison since I was nineteen years of age, and during that time I have known what it meant to endure suffering. I have passed through all sorts of experiences and have often been urged to repent of my sins. In spite of this, however, I did not repent, but, on the contrary, became more and more hardened. And then, by the power of that one word of Christ’s, Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do, my unspeakably hardened heart was changed, and I repented of all my crimes. Such power is not in man.’

V

What was it in that dying prayer that so affected Ishii? He was impressed by the possibilities of a cry from the Cross. And, indeed, those possibilities are appalling. Jesus was still the Son of God, and the hands that were nailed to the tree were the creators of both nails and tree. He could have asked His Father and immediately have received more than twelve legions of angels. When they taunted Him on His inability to save himself, He could have left the Cross in an instant, and, with angelic bands for His escort and heavenly music ringing in His ears, could have returned to His Father, leaving the world to its inevitable doom.

Or, without forsaking the work which He had set Himself to do, He might have called down fire from heaven upon His murderers. He might have cried ‘Father, destroy them!’ and withered them where they stood.

Or, without in any way acting inconsistently with His divine nature, He might have cried ‘Father, judge them: vengeance is Thine; do Thou repay!’

But, no! Father, forgive them, he prays, for they know not what they do. Did he scan those murderous faces, listen to their oaths and jests, and wonder what plea He could justly urge in extenuation of their awful deed? There was only one thing to be said on their behalf, and He discovered and presented that one plea. So skilful and masterly an Advocate is He who ever liveth to intercede for us! Forgive them, for they know not what they do! The plea in that prayer broke the heart of Ishii. It went to his soul, he says, like a five-inch nail.

VI

The New Testament of Ishii’s contains a striking statement which, during his last imprisonment, he may have noticed and pondered. It is to the effect that he that is in Christ Jesus is a new creation. It is the only phrase that can possibly convey an impression of the transformation that overcame Ishii. He became literally and actually, a new creation in Christ Jesus. He was made all over again. And, from his point of view, it seemed as if the world about him had been made all over again. ‘It was only after I came to prison,’ he says, ‘that I came to believe that man really has a soul. I will tell you how I came to see this. In the prison yard chrysanthemums have been planted to please the eyes of the inmates. When the season comes, they bear beautiful flowers, but in the winter they are nipped by the frost, and wither. Our outer eye tells us that the flowers are dead, but this is not the real truth. When the season returns the buds sprout once more and the beautiful flowers bloom again. And so I cannot but believe that if God in His mercy does not allow even the flowers to die, there surely is a soul in man which He intends shall live for ever.’ Here was fresh vision vouchsafed to the eyes of this new creation; and, in keeping with it, there was a new and radiant joy in his heart.

‘Today,’ he writes, in that wonderful journal that he kept all through his last imprisonment, ‘today I am sitting in my cell with no liberty to come and go, and yet I am far more contented than in the days of my freedom. In prison, with only poor coarse food to eat, I am more thankful than I ever was out in the world when I could get whatever food I wanted. In this narrow cell, nine feet by six, I am happier than if I were living in the largest house I ever saw. The joy of each day is very great. These things are all due to the grace and favour of Jesus.’ The Governor of the prison, Mr. Shirosuke Arima, heard of Ishii’s extraordinary bearing, and decided to visit him. ‘One day,’ he tells us, ‘I went to see Ishii in his cell and found him sitting bolt upright and looking very serious. My first glance showed him to be a powerfully built fellow, with heavy bushy eyebrows and a large flat nose. I could not help thinking that, if his heart were as rough as his exterior, one would have every right to fear him. But his eyes told a different story. They shone with a quiet beautiful light; his cheeks were clear and healthy looking, and his spirit was brimming over with gentleness. My heart went out to him with a great tenderness.’

Miss Macdonald was Ishii’s last visitor. ‘We both knew,’ she says, ‘that it might be the last time. I read to him words that were penned centuries ago; but as I stood there in a tiny cubby-hole, and talked to him across a passageway and through a wire screen, it seemed impossible to believe that they were not written for the very conditions that we faced there in that Japanese prison-house. “I have finished all my writing,” Ishii told me, “and my work is done. I am just waiting now to lay down this body of sin and go to Him.” I looked at him and his eyes were glowing with joy.’ He had not long to wait.

‘This morning,’ wrote the Buddhist chaplain, in sending Miss Macdonald Ishii’s journal and effects, ‘this morning Tokichi Ishii was executed at Tokyo prison. He faced death rejoicing greatly in the grace of God and with steadiness and quietness of heart. His last request was that you be told of his going, and be thanked for your many kindnesses. He has left his books and his manuscripts to you, and you will receive them at the prison office. His last words, which are in the form of a poem, he asked me to send to you. They are as follows:

My name is defiled,

My body dies in prison,

But my soul, purified,

Today returns to the City of God!

‘Ishii seemed to see nothing but the glory of the heavenly world to which he was going. Among the officials who stood by and saw the clear colour of his face and the courage with which he bore himself, there was no one but involuntarily paid him respect and honour.’ The Gentleman in Prison, released from the cage of his early conditions, and released from the prison bars that hedged him in in later years, was gloriously free at last!